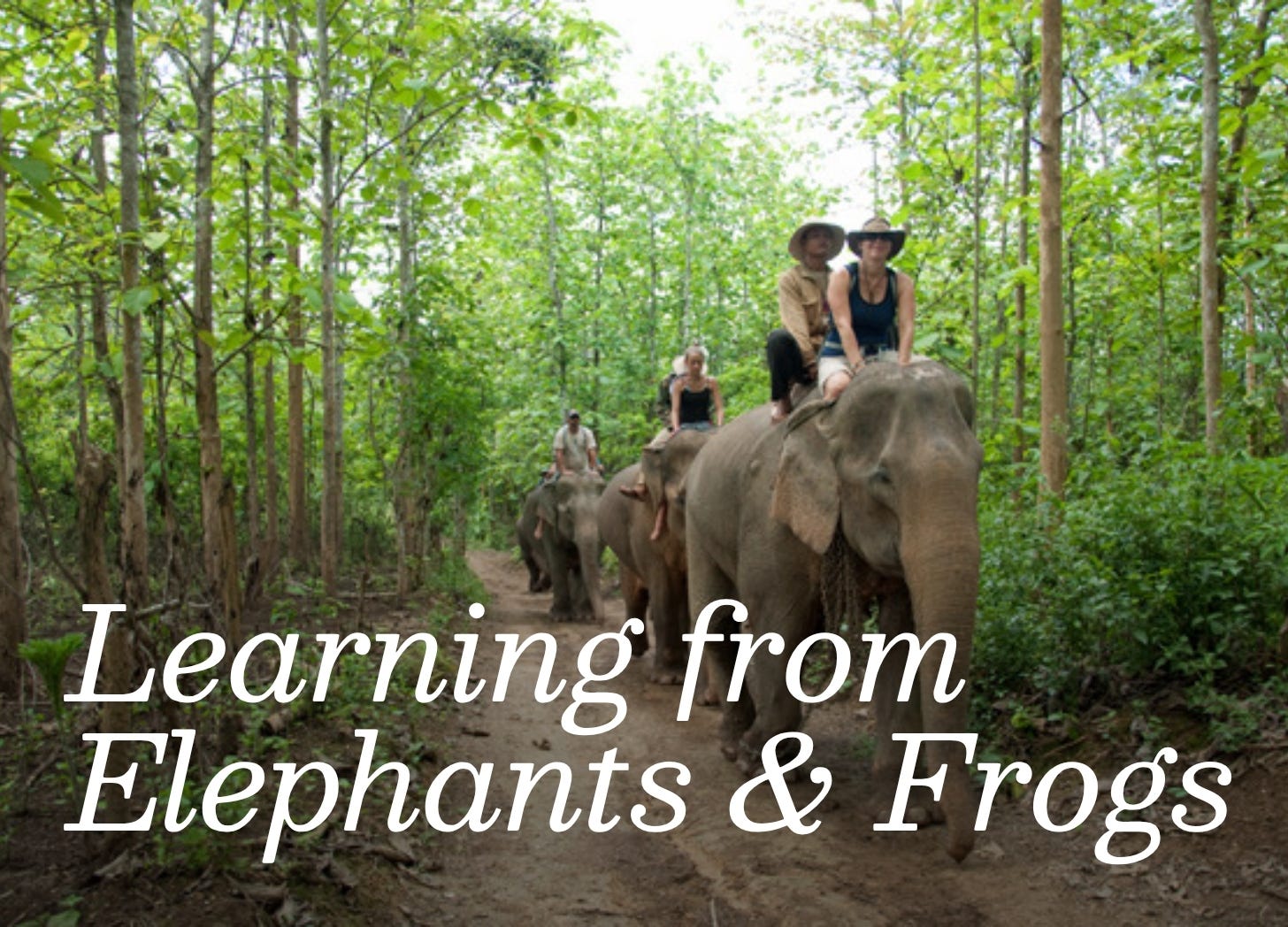

Learning from Elephants & Frogs

An Adventure A Week

While traveling in Laos, I met an elephant called Mae Nam. She was 51 years old and had a 2-year-old infant. Mae Nam was the matriarch of the herd and displayed characteristics that can be associated with a boss: aggression, dominance, and general orneriness.

I met Mae Nam while visiting Elephant Village, an elephant sanctuary several hours outside of Luang Prabang, Laos’s delightful second city. The sanctuary was on the banks of the Khan River, in the shadow of the Namno Mountain range and surrounded by lush jungle.

In the early 1800s, the camp was a training site for elephants participating in the royal procession. Known then as the “Land of a Million Elephants,” Laos revered its national icon. Sadly, today the number of wild elephants in Laos has fallen to less than 1,000.

Elephant Village’s mission is to rescue elephants and provide them a new home where they are free from heavy work such as hauling logs through the forest. Instead, they earn their keep by giving rides to tourists. Our tourist dollars help pay for the elephants’ food and care—which is substantial. Each day an elephant consumes at least 550 lbs. (250 kg.) of grasses, bark, leaves, and fruit.

Side Note: At the time, I felt good about helping support the sanctuary and was thrilled to be able to get up close and personal with the elephants. But since my stay at Elephant Village, my view has evolved.

While I still support the need for an elephant refuge and am happy to contribute to their care, I no longer agree with tourists like me riding elephants. These large gentle animals shouldn’t need to perform for our amusement (no matter how well-intentioned). Instead, they deserve to be free from abuse and hardship and live out their days in a natural environment.

Caring for the elephants are mahouts, or trainers, who stay with the elephants their entire life. Mae Nam’s mahout is Ker. He has been with her for the last eight years and accepts her idiosyncrasies.

Each of us became acquainted with our elephants as we rode them around camp. Riding an elephant is trickier than it initially appears. First, an elephant is pretty tough to get on. I tried several times, but in the end, I needed an extra push to get up high enough to swing my leg over. Sometimes your elephant will cooperate by lying down or bending on one knee. If this happens, you step on her lower leg and pull yourself up by her ear.

To control the elephant, the mahouts carry a mean-looking metal hook like a giant knitting needle that they jab behind the elephant’s ear. The sharp pain stops the elephant from running away. I found it distressing to watch Ker repeatedly resort to the hook with Mae Nam. (See my note above about the unnecessarily harsh treatment of many elephants in captivity, even sanctuaries.)

We spent the day by the side of our mahouts, helping care for our new charges. By late afternoon a group of ten of us rode our elephants across the river and into the jungle to tuck the elephants in for the night at a safe distance from the village. The sanctuary elephants were chained so they couldn’t wander and damage the surrounding villages. Again, the heavy chains around each elephant’s neck were hard to see.

The next morning, with dawn breaking through the dense trees, we set off on the long hike back into the jungle to meet up once again with our trunked friends. Riding the elephants back, we crossed a river, where we stopped to give them their morning bath.

Elephants clearly love water, submerging themselves and swishing their tails as we used stiff brushes to scrub the top of their heads and behind their ears. Elephants will wallow in the water for as long as you let them and we let them soak and splash for more than an hour.

Mae Nam was especially fond of the bathing ritual and liked to submerge herself in the water, with Ker and me standing high on her back trying in vain to keep from falling in.

During my short elephant-sitting session, I not only formed a bond with Mae Nam, but also a healthy respect for her size, intelligence, and individual personality.

If she flapped her ears and swayed her trunk and tail, these were signs that Mae Nam was relaxed. However, if she suddenly stopped and stood still, staring intently, or put her trunk in her mouth, it was time to hand the reins over to her trained handler.

After our days spent with the elephants, we guests enjoyed ourselves at the sanctuary lodge, where we dined on an open-air veranda overlooking the Nam Khan River. My fellow guests and I would meet up each evening, lingering at the communal dinner tables and swapping travel stories at sunset.

One night, as we were settling into our chairs after dinner, our guide asked if he could borrow the headlamps many of us travelers relied on to get about after dark.

The kitchen crew wanted to go bullfrog hunting and the lamps were the perfect instrument, allowing them to stun the frogs with the bright light while leaving one’s hands free to scoop up the jumping amphibians.

A little less than an hour later, our kitchen crew returned with their apron pockets stuffed with big, meaty bullfrogs. We heard them, animated and laughing in the kitchen, enjoying their own dinner party and froggy feast.

Our Laotian hosts may have picked up the taste for frog legs during French colonial times. However, I believe a more plausible explanation is that the locals learned to eat frogs during the hard years when the U.S. military was fighting its secret war in the Laotian countryside during the 1960s and early 1970s.

The frog feast triggered recollections of stories I had heard of my own family’s readiness to eat alternative forms of food in lean times. For instance, during the Depression, my mother’s family—not long after arriving from their homeland of Slovakia—took to raising frogs in their suburban Akron, Ohio basement. The croaking creatures provided the family a source of sustenance during those hungry years.

On our last evening at the elephant camp, a power outage forced us to reluctantly abandon the revelry of the communal dining room. A common enough occurrence in the middle of the thick Laotian jungle, we all returned to our rooms early and went to bed.

Before tucking myself into the mosquito netting, I put on my headlamp and made a trip to the bathroom below my room, at ground level. When I returned, I snuggled down and read by the light of my headlamp, drifting off to sleep.

Sometime in the middle of the night, the power snapped back on. Groggily, I made my way to hit the light switch and then stumbled back to bed. In my half-asleep state, it didn’t dawn on me to check whether or not the bathroom light had also flickered on. It had, and unfortunately, I’d left the door slightly ajar. Room enough to let in the critters.

The next morning, barely awake and rubbing my eyes, I was dumbstruck when I returned to the downstairs water closet. Drawn by the bright light, a horde of termites had swarmed the small commode, covering the tile and fixtures several inches deep.

The critters crunched underfoot as I took to the toilet, where I carefully hovered over the insect-encrusted seat. A shower was out of the question and I even vacated the inundated space to brush my teeth, opting instead to use bottled water and spit toothpaste foam from the relative safety of my veranda.

Packing to leave later that morning, I had no idea how to clean up the massive pile of insects. I was appalled at the mess I’d caused for the cleaning crew and assumed that someone would have to hose down the restroom, sweeping the soggy insects down the drain. But I was wrong.

On my way to breakfast, I passed two Lao ladies rushing toward my bathroom. They were carrying trays full of winged termites, salvaged from another lighted latrine. They then went to work on my overrun washroom, meticulously lifting each termite by its wings and placing them on their trays.

“They were painstakingly picking through the carnage to find the ones that were still alive,” I said to a German traveler over breakfast. “I can’t imagine why.”

She explained to me that what I considered a terribly messy mishap was a boon for our Laotian hosts. Winged termites are a local delicacy, and I had unwittingly provided an opportunity for them to collect hundreds. The barely alive insects were soon headed to the grill to be roasted over an open flame.

Like frogs, insects are considered a rich source of nutrients for those impoverished in Laos. Even today, many Laotians continue to suffer from chronic food shortages. The harsh conditions that began with the secret American war and perpetual bombings continued under the rule of their own communist government. Adding to the misery was an international embargo that denied the starving country aid for decades.

Having endured years of economic isolation, Laos is still dealing with crushing poverty. And, as so often happens, the normal folk are the ones paying the highest price.

Faced with years of starvation, Laotians have adapted their diet to include sources of food that they may not have eaten in the past. Bugs and frogs are no longer jungle pests but prizes that can fill a bloated belly and provide desperately needed nutrition.

It was sobering to see how their eating habits had changed due to decades of hunger. Reflecting on the excitement of our kitchen crew, elated with the capture of their frogs, and the cleanup crew preparing for a winged BBQ, was a stark reminder of a grim reality.

Thinking back on this time, I gleaned valuable insight into how people throughout the world perceive food and gained a new perspective on one of our most basic human needs—to eat and feed one’s family.

When a population is reduced to eating insects to stay alive, in my mind, you’ve crossed over to another level of poverty. My initial disgust with the winged termite infestation led me to personal discovery and a deeper understanding of the extent and power of hunger. And even though I wasn’t hungry, I was nevertheless served another large slice of humble pie. 🦋

Have you ever participated in a tourist activity that you later regretted? What changed your mind? Did you adjust your behavior, and if so, how?

⭐ An Adventure A Week is a serial based on my autobiography “Adventures Of A Nomad: 30 Inspirational Stories.” You can read the essays in order (or not). Can’t wait for the next installment? Get the book.

Christened “Wander Woman” by National Geographic, Erin Michelson is a professional speaker and author of the Nomad Life™ series of travel books and guides, including the #1-ranked “Explore the World with Nomads.”

Hi Rebecca, Thanks for your comment. I'm glad we agree that traveling is all about opening up our minds and evolving as we continue to see more and learn. And yes, I think you're right, that I'm viewing eating insects from a narrow lens. I'm vegetarian, so definitely not for me, but can certainly see how they could be a delicacy or primary source of protein for others.

First off, I love that you added the note about what you've come to believe about elephants. I think it's extremely important for people to embrace the process of change, and I'd love to hear more about how your beliefs evolved!

Secondly, I wanted to comment about your responses to the insect-eating in Laos. It seems to be predicated on two assumptions:

1) Insect-eating is a product of recent deprivation.

2) No one would every eat insects unless they had no other choice.

In regards to 1): Did you read things or talk to Laotians who told you that this was recent? Because the threat of starvation has been a periodic part of life for a long time. I'm not going to say the events of the 20th century weren't bad, but I'd like evidence that insect-eating doesn't trace to starvation issues before the 20th century.

In regards to 2), I fundamentally disagree with this one. If you look at the world, there are many more people who do eat insects than people who don't--if anything, Europeans and North Americans are the outliers! As you pointed out, insects are a good source of protein. If cooked well they can be delicious. Culture informs everything we see as "edible," and if you push far enough back, all food consumption goes back to fear of starvation.

None of the people you talk about were facing starvation as they eagerly anticipated a termite feast--I'll be honest, looking on their enthusiasm with historically-inflected pity really rubs me the wrong way.